-

Study

-

Quick Links

- Open Days & Events

- Real-World Learning

- Unlock Your Potential

- Tuition Fees, Funding & Scholarships

- Real World Learning

-

Undergraduate

- Application Guides

- UCAS Exhibitions

- Extended Degrees

- School & College Outreach

- Information for Parents

-

Postgraduate

- Application Guide

- Postgraduate Research Degrees

- Flexible Learning

- Change Direction

- Register your Interest

-

Student Life

- Students' Union

- The Hub - Student Blog

- Accommodation

- Northumbria Sport

- Support for Students

-

Learning Experience

- Real-World Learning

- Research-enriched learning

- Graduate Futures

- The Business Clinic

- Study Abroad

-

-

International

International

Northumbria’s global footprint touches every continent across the world, through our global partnerships across 17 institutions in 10 countries, to our 277,000 strong alumni community and 150 recruitment partners – we prepare our students for the challenges of tomorrow. Discover more about how to join Northumbria’s global family or our partnerships.

View our Global Footprint-

Quick Links

- Course Search

- Undergraduate Study

- Postgraduate Study

- Information for Parents

- London Campus

- Northumbria Pathway

- Cost of Living

- Sign up for Information

-

International Students

- Information for International Students

- Northumbria and your Country

- International Events

- Application Guide

- Entry Requirements and Education Country Agents

- Global Offices and Regional Teams

- English Requirements

- English Language Centre

- International student support

- Cost of Living

-

International Fees and Funding

- International Undergraduate Fees

- International Undergraduate Funding

- International Masters Fees

- International Masters Funding

- International Postgraduate Research Fees

- International Postgraduate Research Funding

- Useful Financial Information

-

International Partners

- Agent and Representatives Network

- Global Partnerships

- Global Community

-

International Mobility

- Study Abroad

- Information for Incoming Exchange Students

-

-

Business

Business

The world is changing faster than ever before. The future is there to be won by organisations who find ways to turn today's possibilities into tomorrows competitive edge. In a connected world, collaboration can be the key to success.

More on our Business Services-

Business Quick Links

- Contact Us

- Business Events

- Research and Consultancy

- Education and Training

- Workforce Development Courses

- Join our mailing list

-

Education and Training

- Higher and Degree Apprenticeships

- Continuing Professional Development

- Apprenticeship Fees & Funding

- Apprenticeship FAQs

- How to Develop an Apprentice

- Apprenticeship Vacancies

- Enquire Now

-

Research and Consultancy

- Space

- Energy

- AI and Tech

- CHASE: Centre for Health and Social Equity

- NESST

-

-

Research

Research

Northumbria is a research-rich, business-focused, professional university with a global reputation for academic quality. We conduct ground-breaking research that is responsive to the science & technology, health & well being, economic and social and arts & cultural needs for the communities

Discover more about our Research-

Quick Links

- Research Peaks of Excellence

- Academic Departments

- Research Staff

- Postgraduate Research Studentships

- Research Events

-

Research at Northumbria

- Interdisciplinary Research Themes

- Research Impact

- REF

- Partners and Collaborators

-

Support for Researchers

- Research and Innovation Services Staff

- Researcher Development and Training

- Ethics, Integrity, and Trusted Research

- University Library

- Vice Chancellors Fellows

-

Research Degrees

- Postgraduate Research Overview

- Doctoral Training Partnerships and Centres

- Academic Departments

-

Research Culture

- Research Culture

- Research Culture Action Plan

- Concordats and Commitments

-

-

About Us

-

About Northumbria

- Our Strategy

- Our Staff

- Our Schools

- Place and Partnerships

- Leadership & Governance

- University Services

- Northumbria History

- Contact us

- Online Shop

-

-

Alumni

Alumni

Northumbria University is renowned for the calibre of its business-ready graduates. Our alumni network has over 253,000 graduates based in 178 countries worldwide in a range of sectors, our alumni are making a real impact on the world.

Our Alumni - Work For Us

A Northumbria University researcher is part of a team that has produced the first physics-based quantifiable evidence that thinning ice shelves in Antarctica are causing more ice to flow from the land into the ocean.

Their findings have been published in Geophysical Research Letters.

Satellite measurements taken between 1994 and 2017 have detected significant changes in the thickness of the floating ice shelves that surround the Antarctic Ice Sheet. These shelves buttress against the land-based ice, holding them in place like a safety band.

While it has been suggested that the thinning ice shelves were responsible for a direct loss of ice from the land-based ice sheet into the ocean, there was no actual evidence linking data and physics that could demonstrate this, until now.

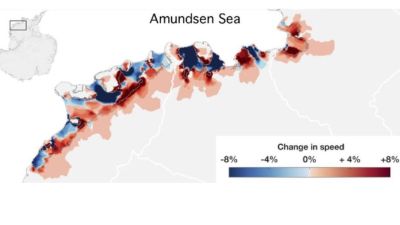

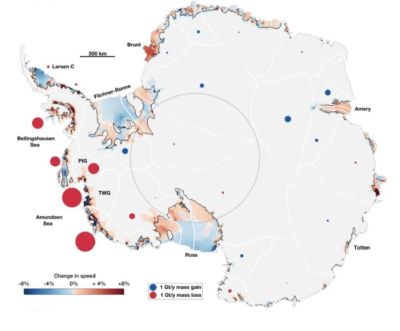

Researchers in the UK and US have now undertaken the first continent-wide assessment of the impact the thinning ice shelves are having on the flow of ice in Antarctica.

They were particularly interested in seeing how much ice flowed across the ‘grounding line’. This is the point where the land-based ice sheet meets the sea-based ice shelves.

They used a state-of-the-art ice-flow model developed at Northumbria and newly available measurements of changes in the geometry of ice shelves to calculate the changes in grounded ice flow.

When the modelled results were compared with those obtained by satellites over the last 25 years, the researchers found what they described as ‘striking and robust’ similarities in the pattern of ice flowing from the ice sheet into the ocean.

The largest impact was found in West Antarctica, which already makes a significant contribution to sea level change. The largest changes are taking place around the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers. On Pine Island Glacier, evidence of these changes could be seen almost 100 miles (150km) inland, upstream of the grounding line.

Hilmar Gudmundsson, Professor of Glaciology and Extreme Environments, led the study. He said there has been a long-standing question as to what was causing the changes we have observed in land-based ice over the last 25 years, and that while the thinning of the floating ice-shelves had been suggested as a reason, the idea had never been put to the test before now.

“I found it striking how well our modelled changes agree with the pattern of observed mass loss,” he said.

“There are other processes in play as well, but we can now state firmly that the observed changes in ice-shelves do cause significant changes over the grounded ice, speeding up its flow into the ocean.”

A critical element of the findings was the speed at which the ice flowed from the sheet into the ocean as a result of the thinning ice shelves.

“One of the most important lessons from this study is that the impact is felt without any delay,” said Professor Gudmundsson.

“Generally, we distinguish between an instantaneous response or a delayed, transient response. Our study shows the thinning of the ice shelves results in a significant instantaneous response to ice flow and ongoing mass loss. This means that we are not protected against the impact of the Antarctic Ice Sheet on global sea levels by a long response time.”

He added: “This study closes an important hole in our understanding. Lack of data and limitations in modelling previously made it challenging to quantify the importance of ocean-induced changes as a driver for ongoing mass loss, but we have now shown that the observed ice shelf changes do indeed impact on upstream flow significantly.”

The research was led by Northumbria University, together with the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

Helen Amanda Fricker, Professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said: “Ice shelves are the most vulnerable parts of Antarctica’s ice sheet system and we know that they are shrinking, but what we didn’t know before this work was how that was impacting the grounded ice behind them.”

Fernando Paolo, postdoctoral scholar at Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, added: “It is striking how far inland the changes in ice shelves can impact the ice sheet flow. Since we now know that shrinking ice shelves are directly responsible for increases in ice discharge to the ocean, it is important that we keep monitoring them to watch how they evolve.”

It is believed that the ice shelves may be thinning due to changes in ocean heat content, either by ocean warming or from changes in how the ocean circulates around and below the shelves, but further research is needed to establish the specific reasons.

The study, Instantaneous Antarctic ice-sheet mass loss driven by thinning ice shelves is published in Geophysical Research Letters.

It was partially funded through both the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration’s PROPHET project and through the recently announced TiPACCs study, which are respectively funded by the Natural Environment Research Council/National Science Foundation and European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

Northumbria University is quickly becoming known as one of the world’s premier institutions specialising in the impact of climate change in our polar regions. It is the only UK university to be involved in two of the £20 million International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration research projects and has recently made impactful announcements relating to Antarctic research. These include evidence of the imminent break-off of the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is twice the size of New York City, and the discovery of three giant canyons buried deep under the Antarctic ice. Last month it was announced that Northumbria has been awarded £1.2 million to investigate tipping points on the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Geography At Northumbria University Encompasses All Of Our Work In Physical And Human Geography, Environmental Science And Management, Health & Safety, And Disaster Management.

Professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences.

This is the place to find all the latest news releases, feature articles, expert comment, and video and audio clips from Northumbria University

News

- First cohort of Civil Engineering Degree Apprentices graduate from Northumbria

- Venice Biennale Fellowship

- Northumbria expands results day support for students

- Northumbria academic recognised in the British Forces in Business Awards 2025

- £1.2m grant extends research into the benefits of breast milk for premature babies

- Northumbria graduate entrepreneur takes the AI industry by storm

- Study identifies attitudes towards personal data processing for national security

- Lifetime Brands brings student design concept to life

- New study reveals Arabia’s ‘green past’ over the last 8 million years

- How evaluation can reform health and social care services

- Researchers embark on a project to further explore the experiences of children from military families

- Northumbria University's pioneering event series returns with insights on experiential and simulated learning

- Support for doctoral students to explore the experiences of women who have been in prison

- Funding boost to transform breastfeeding education and practice

- A new brand of coffee culture takes hold in the North East

- BBRSC awards £6m of funding for North East Bioscience Doctoral Students

- £3m funding to evaluate health and social care improvements

- Balfour Beatty apprentices graduate from Northumbria University

- Long COVID research team wins global award

- Northumbria researchers lead discussions at NIHR event on multiple and complex needs

- Healthcare training facility opens to support delivery of new T-level course

- Young people praise Northumbria University for delivery of HAF Plus pilot

- Nursing academics co-produce new play with Alphabetti Theatre

- Research project to explore the experiences of young people from military families

- Academy of Social Sciences welcomes two Northumbria Professors to its Fellowship

- Northumbria University set to host the Royal College of Nursings International Nursing Research Conference 2024

- 2.5m Award Funds Project To Encourage More People Into Health Research Careers

- Advice available for students ahead of A-level results day

- Teaching excellence recognised with two national awards

- Northumbria law student crowned first Apprentice of the Year for the region

- Northumbria University launches summer activities to support delivery of Holiday Activities and Food programme

- UK health leader receives honorary degree from Northumbria University

- Use of AI in diabetes education achieves national recognition

- Research animation explores first-hand experiences of receiving online support for eating disorders

- Careers event supports graduate employment opportunities

- Northumbria University announces £50m space skills, research and development centre set to transform the UK space industry

- The American Academy of Nursing honours Northumbria Professor with fellowship

- New report calls for more support for schools to improve health and wellbeing in children and young people

- AI experts explore the ethical use of video technology to support patients at risk of falls

- British Council Fellows selected from Northumbria University for Venice Biennale

- Prestigious nomination for Northumbria cyber security students

- Aspiring Architect wins prestigious industry awards

- Lottery funding announced to support mental health through creative education

- Early intervention can reduce food insecurity among military veterans

- Researching ethical review to support Responsible AI in Policing

- Northumbria named Best Design School at showcase New York Show

- North East universities working together

- Polar ice sheet melting records have toppled during the past decade

- Beyond Sustainability

- Brewing success: research reveals pandemic key learnings for future growth in craft beer industry

- City's universities among UK best

- Famous faces prepare to take to the stage to bring a research-based performance to life

- Insights into British and other immigrant sailors in the US Navy

- International appointment for law academic

- Lockdown hobby inspires award-winning business launch for Northumbria student

- Lasting tribute to Newcastle’s original feminist

- Outstanding service of Northumbria Professor recognised with international award

- Northumbria academics support teenagers to take the lead in wellbeing research

- Northumbria University becomes UK's first home of world-leading spectrometer

- Northumbria's Vice-Chancellor and Chief Executive to step down

- Out of this world experience for budding space scientists

- Northumbria engineering graduate named as one of the top 50 women in the industry

- Northumbria University signs up to sustainable fashion pledge

- Northumbria demonstrates commitment to mental health by joining Mental Health Charter Programme

- Virtual reality tool that helps people to assess household carbon emissions to go on display at COP26

- EXPERT COMMENT: Why thieves using e-scooters are targeting farms to steal £3,000 quad bikes, and what farmers can do to prevent it

- Exhibition of lecturer’s woodwork will help visitors reimagine Roman life along Hadrian’s Wall

- Students reimagine food economy at international Biodesign Challenge Summit

- Northumbria storms Blackboard Catalyst Awards

- Breaking news: Northumbria’s Spring/Summer Newspaper is here!

- UK’s first ever nursing degree apprentices graduate and join the frontline

- Massive decrease in fruit and vegetable intake reported by children receiving free school meals following lockdown

- Northumbria awards honorary degrees at University’s latest congregations

Geography At Northumbria University Encompasses All Of Our Work In Physical And Human Geography, Environmental Science And Management, Health & Safety, And Disaster Management.

Professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences.

This is the place to find all the latest news releases, feature articles, expert comment, and video and audio clips from Northumbria University

Latest News and Features

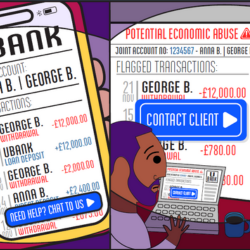

Report calls on the UK banking industry to consider interventions that "design out" economic abuse

Researchers have published the findings of a ground-breaking study which brought together victim-survivors…

.png?modified=20251222122622)

Northumbria's ‘Banana Split: Unpeeling a New Energy Source’ project highly commended at prestigious Green Gown Awards

A Northumbria University research project has been highly commended at the 2025 Green Gown…

Northumbria ranked most sustainable university in the North East for fifth consecutive year

Northumbria University has been rated as ‘1st class’ for sustainability and is once again the…

Northumbria expert delivers training to help address victim-blaming language

A Northumbria University academic is leading pioneering training to support police forces across…

Northumbria University launches national AI challenge inviting young people to imagine a hopeful future

Northumbria University has launched the Hopeful Futures AI Challenge, a groundbreaking national…

Student volunteering partnership expands following five years of community impact

Following the success of a Law in the Community project, Northumbria University is expanding…

Funding awarded for innovative space technology projects

The North East Space Communications Accelerator (NESCA) has successfully awarded its first…

First cohort of Civil Engineering Degree Apprentices graduate from Northumbria

The inaugural cohort of Civil Engineering degree apprentices have graduated from Northumbria…

Upcoming events

Collaborating for Capability: Shaping the Future of Supply Chain Talent

City Campus East, Northumbria University CCE1-403

-

Archives to Action: Historical Evidence for Policy Reform

Virtual Workshop

-

Viruses of Microbes-UK (VoM-UK) Conference 2026

Northumbria University

Commercialising SHAPE Innovations and Impact

Northumbria University

-